Civics on the Rocks: Is It Supposed to Rain This Weekend?

- Anne Trominski

- Apr 25, 2025

- 36 min read

By Anne Trominski:

In case you were unaware, things are a bit crazy in the United States right now. In an era of shocking news stories, unheard of court cases, and generally unprecedented political events, discourse has gotten a tad tense . . . some might even say divisive.

Can we still discuss the events of the day over the dinner table? Can we realistically look to the past to deal with the problems of today? Is there an appropriate cocktail to serve for the end of times?

Three friends tackle these topics and distract themselves with other tangents in their podcast Civics on the Rocks. Steve’s an engineer, Mack’s a history teacher, and Anne’s just trying to get the mics to work correctly (with varying amounts of success). The long-form episodes are released at the beginning of each month. Living in Texas, they have plenty of political fodder to chew on, but topics cover all types of history and government. The hosts are unrepentant geeks, so they are just as likely to drop movie references as knowledge bombs but, ultimately, their goal is to try and figure out how to be engaged citizens in modern America. They’re also drinking and making cheesy jokes while doing it.

Full episodes with citations (geeks, I say) are available on their website, CivicsOnTheRocks.podbean.com, as well as all the major podcast carriers and socials.

In this episode, the trio discuss the vital roles played by the National Weather Service and NOAA and their effects on our lives and safety.

Read the edited transcript or listen to the entire episode below. And click here for references to the facts and topics discussed throughout.

This episode originally aired April 7, 2025.

Anne: The question of the day. Is it supposed to rain this weekend?

Mack: Here? No. But somewhere? Yes.

Steve: How can you be sure?

Anne: How do you know?

Mack: Well, because there have been warnings put out. Warnings, actually, now that you mention it, from the National Weather Service. And to be specific, this is the first time that they've had, like, a warning for a tornado outbreak a day in advance. It's only like the third time since 2006, and it's basically going to be affecting the states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama. But it is like their highest-level warning for, like, there will be a tornado outbreak tomorrow in those states. And it's in part because there's a front that was going across Texas today for which we had a warning in advance from the same agency, National Weather Service, about hurricane-force winds going across the panhandle of Texas and then down into, like, Edwards Plateau of . . . Yeah, where they, in fact, there's footage today of 18 wheelers literally getting blown off the road around Amarillo and police closing some interstates just because of the number of wrecks that they had. And there's a massive dust storm up there now. That front is going to be over those states tomorrow.

Anne: Wow. So it sounds like hearing about the weather in advance is really handy if there's an emergency situation.

Mack: It is. I mean, it's the main thing is to save lives and --

Steve: And property.

Mack: And property. And help the wheels of commerce continue.

Steve: So there’s an economic value in that?

Mack: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah.

Steve: People should pay for it. Shouldn’t just be given away for free.

Mack: So. Well, you know what? And strictly speaking, it's not because our tax dollars pay for it. Our tax dollars . . . it sounds like a Captain Kangaroo segment. Like we're explaining the National Weather Service.

Anne: Yeah. I was wondering how long you guys were going to be able to maintain that tone.

Mack: Yeah, well, right until then. So, you know, we have the National Weather Service --

Anne: Can we return back to sarcasm and . . . ?

Mack: Yeah, sure.

Steve: Getting back to our natural state.

Mack: So we pay for the National Weather Service, and it's part of NOAA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And they're in the Department of Commerce, and in part because . . .

Steve: Which on the face of it, would be weird. You’re thinking this is a whole sciencey agency . . .

Mack: But this is science, this is weather. It’s like, well, there is a benefit to commerce in the United States for businesses, including major businesses, to be aware of things like hurricane landfalls or tornado outbreaks or dust storms or massive snowstorms . . .

Steve: Droughts.

Mack: Or droughts, freezes, wildfire dangers, that sort of thing. And yes, it is, you know, the main thing . . .

Steve: Storms at sea, shallow, yeah. Whatever you call it, when there's not much water out there to keep the boat afloat.

Anne: Low tide?

Steve: Well, the tides, but more, no, the bathymetry? Where they monitor the depth . . .

Mack: You're the engineer.

Steve: Yeah, but not that kind of engineer. Well, no, but they direct their soundings to measure the ocean floor, and things like that, to make sure the sea is navigable.

Mack: Yeah. Well, actually, yeah, that is one of NOAA's responsibilities. NOAA was created in 1970, and it was sort of, that there were other services that got all put under NOAA.

And NOAA, incidentally, is one of the, outside the military, is one of two uniformed services, the other’s the Public Health Service. And that's because, now that doesn't mean that everybody [who] works at NOAA is wearing a uniform. But NOAA has ships, has their own small fleet of ships that do things like soundings.

Anne: The Public Health Service has uniforms?

Mack: Yeah.

Steve: A friend of ours works for them actually.

Anne: Huh. Okay. Sorry.

Mack: Yeah.

Steve: And ranks and whatnot.

Mack: Yeah.

Anne: Really?

Mack: Yeah. Both Public Health Service and NOAA use naval ranks . . .

Anne: Is that why we have a Surgeon General?

Mack: Yeah.

Steve: Yep.

Anne: Wow. I'm learning so much tonight. Please continue.

Mack: But they, and it's weird, though, because they use Navy uniforms.

Steve: Yeah.

Mack: And I want to say they have naval ranks, but the Surgeon General is a Surgeon General.

Steve: Yeah. It’s, you know . . .

Mack: Anyway . . .

Anne: So the Surgeon General hasn't always been part of the Navy?

Mack: No.

Anne: I’m sorry, I always thought the Surgeon General was a member of the military.

Mack: Well, not, they don't have, they could be. They don't have to be.

Anne: Wow. I never knew that. Sorry. This is an exciting podcast.

Steve: The Uniform Service, not military, was a thing I wasn't aware of until probably 10 or 15 years ago. It was like, wait, they’re what? And what, why? Yeah. So.

Mack: Yeah. So anyway, you know, NOAA has ships that will go out and do soundings, in order to have the nautical charts that have the depths and that sort of thing for harbors and coastal waterways and that sort of thing for, you know, so ships don't run aground.

Steve: “Aground.” That was the word I was looking for earlier. “Ship no floaty no more” actually should have been “run aground.” Yeah, that was the . . .

Mack: Oh, my god. Is this when we tell our listeners that we started drinking before we start?

Anne: No, that's the next segment. Stay focused on the weather.

Steve: So in addition to the oceanography, bathymetry, and all that sort of stuff, again, ocean currents and whatnot, they also track the weather. And we actually shouldn't overlook tsunami warnings.

Mack: Oh, yeah.

Steve: Which is kind of the interface between the two.

Anne: But earthquakes are a different agency.

Mack: U.S. Geological Survey. Is that it? The U.S. Geological Survey?

Steve: “Service,” I think.

Mack: Ok.

Steve: I think it’s “service.”

Mack: Oh, yeah. Because the survey is the . . . Yeah.

Anne: The survey is the thing the service does.

Mack: Right. Sounds good.

Steve: By the seashore.

Mack: So, I mean, one of, the main thing is to save lives, because there have been numerous events where it was recognized the value of having good weather forecasting and a warning system in place and an alert system and that sort of thing. But also that it, I mean, it definitely has an impact on commerce in the United States. And so NOAA's part of the Department of Commerce and so is the National Weather Service. [The] National Weather Service actually originally started as part of the Army Signal Corps. It may not have been called Signal Corps then, it was in the 1800s. Because they recognized the [importance] for the military of weather forecasting. And then in 1870, they took it from the Signal Corps to Department of Agriculture. And that makes sense because, I mean, it's definitely valuable for farmers because of rain, drought, everything, and especially because of where most farms are in the United States— tornadoes. And it was part of the Department of Agriculture until, I think, 1940. And it was also called the U.S. Weather Bureau until 1970. And that's when NOAA was formed and gets put under NOAA, and it's called the National Weather Service.

But just one thing to give an example of how the National Weather Service thinks about, and it’s a federal government agency, with their mission of saving lives and providing timely information. There used to be, when we were growing up, you could have a “tornado watch,” “tornado warning.” Okay. And “tornado watch” meant the conditions were right for a tornado; “tornado warning” meant that either on radar they saw a circulation or, like, a tornado was spotted. So there's, like, a tornado in this area. I think it was May 3, 1999, the National Weather Service in Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, there was a massive, you know, F5 tornado that was forming and part of a huge tornado outbreak, and they sort of decided on the spot they needed to—because this is heading for Oklahoma City. This is an F5 not out in farm country but that's heading for a densely populated area. And they decided we need to say something different than just tornado warning. And that's when they use the phrase “tornado emergency” in order to convey the . . .

Steve: The emergency.

Mack: Yeah, the immediacy of the get underground now. And so there were a couple of other times after that that it was used sort of informally, but it was always when there was a major tornado that was near a heavily populated area. And then finally, sometime in their early 2000s, they sort of formalized when they would use “tornado emergency.” So, no, that's a third one where it's like, it's not just a warning, it isn't just like we've seen this on radar. It's big. There is a potential massive loss of life. Get underground now. We're not kidding.

Steve: Yeah, makes sense.

Mack: But you know a lot of this is developed over time in part because of storms that caused a lot of deaths. You know, like here in Texas, there's the Galveston hurricane, which killed anywhere from like 8,000 to 12,000 people. They're not sure. It's still the deadliest weather event in U.S. history.

Anne: I thought Katrina passed it.

Mack: No. Katrina, the death toll estimate at the time was about 1,500. And then I want to say they revised it downward because of, like, multiple people getting reported, people getting reported multiple times. So it ended up being, like, it was over a thousand. But it was not the deadliest.

Steve: But the Galveston one was like 1,900.

Anne: No. Yeah. I read Isaac's Storm, I remember.

Mack: Which is an excellent book, by the way.

Anne: Yeah. It’s a fascinating . . .

Steve: I think Katrina was, like, the deadliest one by far since that one.

Anne: Yeah.

Steve: So in recent times.

Mack: Well, and also, the thing about Katrina—it happened in 2005. We should not have had that kind of a death toll. And it wasn't for lack of warnings. I mean, it was the emergency management of New Orleans, Louisiana, and FEMA, and not to get into, like, who was more at fault, because they all argued.

Anne: Yeah. Everybody kind of fucked that one over.

Mack: Yeah. But for National Weather Service, I mean, we had, like, everybody had timely data. We were watching it on radar. We could see how big it was, that, you know, National Weather Service, as well as all of the, you know, local news stations and Weather Channel and everything were stressing just how bad this could potentially be.

Steve: And that was one where I think that was one of the . . . not the first ones, exactly, maybe first high profile, where they really were doing a better job on talking about storm surge. Because it used to be everyone talked about landfall, which was when the eye hit, and a lot of times communities did not get ready for the storm surge that was hours ahead of that, and a lot of people would get killed because they assumed they had until landfall.

Anne: Right.

Steve: It seems to me Katrina was one of the first times they really promoted no, no, no, this is when the storm surge is going to hit. And because, honestly, they hadn't been able to predict them that well until around that time. In the, I want to say 50s and 60s, there were a few that, they didn't even, like, know. It's kind of been fascinating over the decades because of the sustained attention and investment and effort how much better and better the forecasting, particularly of hurricanes, has gotten.

Mack: Yeah. Well, and also with Katrina was, I remember, in the aftermath of it, there was a thing where they're looking at the storm surge because Katrina, offshore, was Category 5, but by the time it hit, it was Category 3. But, and this was something about, like, the storm surge was more or less getting generated when it was still Category 5. So even though it hit as a Category 3—and the categories, or if you don't know, are based on the wind speed—even though it hit as a Category 3, it was still like a Category 5 storm surge because the levees . . . the levees were built to withstand like a Category 3. But it was . . . So it's like, well, wait, you know, Katrina was a Category 3. Yeah. But right offshore, when it starts generating what becomes the storm surge, it became a Category 5 storm surge.

Anne: Harvey was a Category 5, right? It was bigger than Katrina, but there was less loss of life.

Steve: It was larger than Katrina as far as breadth, I believe.

Mack: The physical size . . .

Steve: But I don’t think it was a 5. . . .

Mack: I want to say that it was a Category 4.

Anne: Okay.

Mack: There were massive flooding from Harvey. The other thing is, is that Houston is not right on the Gulf. And so, but Houston has a lot of areas that will flood and did flood.

Steve: If by, you mean, the entire city of Houston . . .

Mack: Pretty much.

Steve: Yes. That's correct.

Anne: Well, and that was another one where the approval for the infrastructure did not pay any attention to, like, flood plains and what would happen should a hurricane move through there. And . . .

Steve: Yes. And Houston very famously has very loose restrictions on development.

Mack: Or they're always going to side on the what the developers want to build. That sort of thing.

Steve: Yeah. Yeah. I will also say that that storm was, like, also the worst case you could have come up with for Houston.

Anne: Well, yeah, but, like, they found reports later where, like, you know, plenty of very smart people were like, no, you shouldn't build that here because . . .

Mack: You need another reservoir.

Anne: . . . and then they built it there.

Steve: Well, it's amazing the ones where they had the flood-control dams, and then they developed inside the flood-control dams.

Mack: Which is like, not where you’re supposed to . . .

Steve: That's not how that works. But yeah.

Mack: And incidentally, public service announcement . . . Whenever you see the picture, whenever a city has massive flooding, the picture of a shark, you know, floating down the interstate, going like, oh my God, look at that . . . It’s a fake picture. It was used in Harvey. It was used in Ike. It was used in, you know. Yeah. That one's not real. So . . . having said that though, don't go swimming in that water.

Steve: No. There's really bad stuff in flood water. Really bad stuff. As the sewer engineer, I can assure you there are things in flood water you do not want.

Mack: And we're also talking about Houston. The city where shit blows up occasionally here or there in different parts of town. I mean, look, I love Houston. I lived there for 13 years. I do love the city, but . . .

Steve: I grew up there. I don't live there anymore.

Mack: Yeah, well, there's things you have to be aware of if you're going to be a denizen of the greater Houston area. For one thing, it's like the size of Connecticut.

Anne: I was gonna say the greater Houston area is the right side of Texas.

Steve: It’s a swamp.

Anne: It is a swamp.

Steve: They don't have malaria, though. Haven't for a long time.

Anne: Oh, dude, why would you say that right after a measles outbreak?

Mack: Well, those are two different things.

Anne: No. Not anymore. That's what I'm saying is, no disease is off the table anymore. Do not invoke that!

Mack: Well, okay. But I mean, malaria is, they spray for mosquitos . . .

Anne: Dude! We are so going to get malaria in Texas now because of the two of you.

Mack: No.

Steve: Well, if we get it, it's not our fault.

Anne: Dude. The next four years, you want to place money on whether there's going to be a malaria outbreak. You think they're not going to cancel mosquito fogging.

Mack: No, they're not going to cancel mosquito fogging. That's something that's done locally.

Steve: Yeah, Houston pays for that. They're fine.

Mack: Yeah. And the people of Houston recognize the importance of doing that because they don't want to get malaria.

Anne: You’re talking about logic . . .

Mack: Or West Nile.

Anne: . . . during this time frame. You know what else is really handy and a good use of tax dollars? The National Weather Service. I'm sure nobody will cancel that because that helps us with tornadoes and hurricanes.

Mack: It does.

Steve: And enables commerce, which is kind of the funny thing. Like, it's in the Department of Commerce.

Mack: It helps commerce.

Steve: It helps everything. I mean, there are some private companies that I have—we have a good friend who actually is a meteorologist. And it was like, when you graduate with a meteorology degree, 99% of you are going to go work either for the National Weather Service or a TV station. But not all of you, because major corporations employ their own meteorologist. It's that important to know about the weather.

Mack: Like, for real. And the military does too.

Anne: Yeah. Okay. So this is the second time we've had an opening to talk about . . .

Mack: Yeah.

Steve: So I’ll bring it back! So, that's how important weather is to everybody. That is why it's housed under Commerce. It's not just for safety, it's also to make the economy move, allow people to make a living, do it safely, protect their property. And yeah, it's, that's why it makes sense to be a government service.

Mack: Yeah. So . . .

Anne: And yet . . .

Mack: One of the things that's happening in the Trump administration is they—DOGE—set its sights on NOAA and the National Weather Service. And the last I saw, NOAA was going to be firing something like 800 workers, and they're going to put a hiring freeze on, and there were certain programs that were pending that are now . . . not, at least, that's the way, and this is just from like a week or so ago. So this might be another one of those things where they sort of backtrack and, or not, who knows? But some of those 800 workers are with the National Weather Service. Now, even though Trump said during the campaign, “I don't know what Project 2025 is” --

Anne: Nobody’s pretending about that anymore.

Mack: Right. But there was a section on doing away with the National Weather Service for different reasons that were, frankly, bullshit. But at the end it was just like, and also, these services could probably better be provided by private sector. You know, just sort of the unquestioned, you know, the holiness of market forces and not considering whether or not something should actually be a public good, because it would make more sense for not only us as taxpayers but also businesses. Which is one of the things, you know, Project 2025 is like 900-something pages, so I haven't read all of it, but a few things that I've read, it's like these people are not, it's like they're smart to a point, and then they just stopped, and they . . . the idea that private sector would probably be better at this anyway, which is very nearly what it said. And it's like . . . ughh.

Steve: Yeah. Well, especially when you look at like, what do they do? Right. They collect weather data, you know, at every airport and then some all over the U.S. I mean, it's very granular data as far as spatially for many, many points in the U.S., they collect weather continually. They send up weather balloons, like, I think it's twice a day for most locations to get atmospheric profiles.

Mack: And then they actually stopped sending some weather balloons in some locations. Yeah, that was one of the things I got cut.

Steve: And that's not, putting aside their uses of satellites and all that kind of thing to monitor the weather, and then they keep all the data. They process the data over the time. They've invested in the people and the research to come up with ways of predicting and analyzing the weather data. That's all, you know, if you want to say capital investment by the government in the National Weather Service in those systems. And so, A) do you really think a private enterprise is going to maintain that operating expense of all those weather stations and all those far-flung areas and all those people managing them and the data-collection systems? Do you really think they're going to bother, you know, with . . .

Mack: Or if they were, how much are they going to have to charge?

Steve: Yeah. And if you get rid of the National Weather Service and all the expertise that's been built up and a private firm takes over, what have they done? They've basically stolen that capital investment from the American people. You know, we built that knowledge. That's why it should be a public service. Period. When we were talking about this topic, it reminded me—I don't know exactly why, but it did—of firefighters, how back in the olden days, through the 1700s here, it was private firefighters.

There wasn't a city fire department. If you wanted fire-protection services, you paid a company for that, and you would have their little emblem, their medallion on your house. So they knew which houses to protect when they caught on fire or not.

And it continued into the 1800s in London and Australia and so forth, where you would have companies come out to protect your house while your neighbor's house burned, because they didn't pay us. And that's the kind of thing. And then thinking about how, you know, your neighbor's house on fire endangers your house, this is not an isolated kind of thing. And so Benjamin Franklin started the first, I believe, where it was a kind of a citywide everybody in the area gets fire protection. And we've had that ever since, because it makes sense, because when you have that kind of shared risk, shared connection, you need a service that covers everybody. It doesn't make sense to have it, “Oh, well, you paid and they didn't.” Same thing for weather. It's like everybody needs access to weather data for their livelihoods, for their safety.

Mack: And I also want to say that even if somehow this had started back in the 1800s as somebody with an idea of, “I'm going to create a business that's in the business forecasting weather and what we need to do.” Think about the example of AT&T, okay, and how it gets started in the late 1800s, early 1900s and has to, you know, wants to connect every house, every business, every building with phones where everybody can call everybody. And it's a tremendous amount of investment in research, research and development, the science, the engineering, the physical building of the infrastructure and everything. And you might say, well, look, there was one company that did that. Yes, but it was also a monopoly. And people paid through the nose. They were willing to pay through the nose because it was an important service. But at the same time, all the way through the late 70s, AT&T had this relationship with the government of the United States where there was an understanding that they would make the services, you know, as cheap as possible. They would, a lot of the research, you know, the government would have access to for other applications and things like that, especially in wartime. And there was sort of this understanding, and AT&T felt like it was under some pressure to sort of provide certain things that it benefited from, from its research and development and all this other stuff, so that they could maintain the monopoly. So, like, if you're talking about, okay, well, what if somebody started weather forecasting as a business and it became, you know, I would imagine it would have had to have become something like an AT&T. Where it would have sort of naturally become a monopoly eventually. With, you know, the science and technology getting developed but would also need to maintain, like, a special relationship with the government in order for the government not to go after it for antitrust.

Steve: Yeah. It's almost like a, the term “quasi-governmental” isn't usually used for them, but it was sort of, it was awfully close, you know, to the government.

Anne: And, you know, with the weather it's easy to go like, okay, is it raining outside? I'll just go outside and look, you know, what's the big deal? If we had to pay a private company for the weather, and it's, the big deal is always going to come down to the small people, the people that have less money, the smaller businesses, the smaller . . . you know, think about the family farm. The major agricultural businesses can pay a lot of money to find out that, yeah, a drought is forecasted for the next year. Or, you know, we’re only going to get certain types of weather, so we have to plant certain types of crops in response. A small family farm may not be able to afford to pay a private company to have that kind of weather forecasting. And they have to gamble. And the gamble means they might lose the farm next year. And it's always going to be the smaller parts of the population that hurt the most when you privatize things like this.

Mack: Yeah. Well, and also if we're talking about, like, late 1800s when this is starting up, you know, the farms that we had were mostly family farms. Not like big agribusiness that we have today. And so, yeah, you, they would probably not have been able to afford it, especially because, you know, banks were screwing them on loans. Realtors were screwing them on rates at the same time. And, for that matter, you know, not that I've ever been a farmer but, you know, farmers that live near one another, I mean, at least this is true out in the Midwest where my mom's family was from, you know, they are sort of a community where you help each other out. And I imagine even if some farmers could afford, or they'd probably, like, pool their resources in order for, like, one of them to get the subscription to the weather service, and then we'll secretly, you know, share the information with others.

Steve: The co-op subscribes, or whatever.

Mack: Well, the Grange. But yeah, it is when it's our tax dollars paying for it, it ends up being very affordable. But if it's going to be a business, I mean, we don't have any influence over where the business sets up, where they're going to get their data, where they're going to, you know, who they're going to serve, and what their rates are going to be. Now, do we pay for weather apps on our phone? Well, yeah. But that's also, in part, because Congress passed a law preventing National Weather Service from doing it. And so we have some choice in that.

But this is where there's a problem, because there are people who will say and have said that, “What do I care if Trump wants to cut the National Weather Service? I've got the weather on my phone.” That weather data came from the National Weather Service.

Anne: And it's also like, you know, going back to your firefighter example, like, the idea that they would fight the fire for the one house but not the one next to it that would, you know, because they didn't pay for the service. Everybody knows how fire works. If the wind shifts, that fire in that one house is going to go into the house next door, you know, it's going to spread. It doesn't make any kind of logical sense to only fight the fire of the one house. And, I mean, that even applies to these weather situations where it's like, it doesn't make sense for the gated community to evacuate, and then the rest of the community doesn’t. And you have all these problems, you know, then commerce gets impacted, then these businesses get wiped out. Then not, you know . . .

Steve: It makes sense if you're short-sighted and self-interested. That's it.

Anne: If you want the community to thrive, which is, by the way, how you get good commerce and money moving around and prevent disease from spreading and all these things that are going to be real possibilities in our future, you want the good of the community to be paramount. The community needs to thrive for the people within the community at all levels to thrive.

Steve: Which would seem to be self-evident.

Anne: (sighs) There's a lot of scientific research on that. Of course, you know, if you're shutting down the scientific agencies who, you know, monitor that.

Mack: But for anybody that thinks, well, hey, I mean, market forces would just make all of this more efficient, it's like, okay, let's say that they sell off all of the facilities, radar installations, satellites, everything to the highest bidders. And you've got 3 or 4 different major, you know, weather comp[anies], AccuWeather and whoever else, Weather Channel, whoever owns them and buying up the stuff. Okay, well, that means now they're going to be split, and who owns what? How are they going to compete, first of all? Like, how would that work out? Like, what if it's one company buys all the satellites and then another company has all the weather stations in the southeast, and another company owns all the weather stations in the west. And how that's like, I mean to have . . . to get the full benefit, wouldn’t they have to cooperate? You know, which, would you be sort of like going back to a monopoly anyway? And do you think it'd be less expensive than it would for what we're paying for it right now?

Steve: Well, and if it's a private business, one of the reasons you have a private business is because they're allowed to take risks and fail. If you're the weather provider for data for the southeast, and you don't do a good job, because you don't run the business well or whatever, and then you go bankrupt and there is no weather data for the southeast, is that an acceptable outcome? I would argue no, no, it is not. You cannot have weather provided by somebody who might not be there tomorrow.

Mack: You know, when it comes to hurricane seasons and tornado seasons, we want to, like, eliminate the chance of failure.

Steve: Right. And you don't want them to suddenly put up a paywall on hurricane tracking. Well, you know, our day-to-day three-day forecast is free but for the hurricane tracking, you have to pay for premium subscriptions.

Anne: Yeah. If you want to get the tornado alert.

Mack: The watches are free, but the warnings are extra.

Steve: Yeah. I mean, those are the ones that are in high demand. That's the right way to price it.

Mack: Yeah. It's not gouging. It's just what the market will bear.

Anne: And, like, I know Project 2025 was big and lengthy and has, you know, lots of footnotes and looks fancy, but it's not actually well thought out. So for the people out there who are holding out the idea of that, it's okay that the government is doing this. It's okay that DOGE is doing this because they've got a plan that it's going to make it all work. And it's, you know, there's a reason why they're doing all of this that makes sense on a logical level somehow . . . no, nothing they have done thus far supports that. Like, they are comically bad at what they are doing. And there's no reason to think that they have thought any of this through or care that people will get hurt in the short term.

Steve: Well, and it's not even, like, our judgment of that. It's when they've made some radical change and then within 24 hours, they undo it. Covered that last. I mean, it's like there's stuff they've done that they've suddenly realized after the fact that they were wrong, and they backpedaled. I mean, if you have to correct yourself within 24 hours, you didn't have a plan.

Anne: That brings up a point that I was thinking about, because I know that certain of the executive orders are flying in the face of law, of, you know, the president saying, we're not spending the money on this. And it was like, it was never yours to spend. Congress said we’re spending the money, the money gets spent.

Mack: Yeah, already authorized it. It's supposed to . . .

Anne: Yeah. So was what's the case with the National Weather Service? Is that authorized by Congress?

Mack: Well, what it sounds like is it's reducing the number of employees. So, you know, there's money that's been allocated for the National Weather Service and NOAA. And just like with anything else that's already been voted on and passed, that money should go to them. But in terms of firing employees and selling off properties, because there was like a forecast center for NOAA that is on the list of getting . . .

Steve: I saw they were actually closing the severe storm center in Norman, actually, or something.

Mack: Yeah, it was something like that. That was on the list. So you go back to, okay, you know, civil service and whether or not the, you know, Trump can just fire people, or how you would have to—which raises an interesting question, like, if you were actually going to say, all right, we absolutely need to reduce, you know, the number of employees we have in these different agencies, you know, okay, how do we do that? And, I mean, more or less it would have to be done by law.

Steve: One of the interesting analysis I saw, they use the forest and trees metaphor, which is one of those that oftentimes doesn't get used well, but here it is perfect, because it's the individual employees. There's a lot of protection in place as far as civil service law and things like that prevent them from being fired without cause. So you see them trying to skirt that by, we’re firing their probationary employees. Oh, we're saying everybody was a performance problem or whatever. And that's the argument, a lot of the current legal arguments are that, which is on an individual basis. They're saying, oh, well, there's a bunch of individuals, but we're arguing these individuals should not have been fired because it's against the law for those individuals to be fired, which is the trees problem. The forest problem is if you fire all the people in the agency, there's no agency. So you're not firing people, you're destroying an agency that was enacted by Congress. So, at some point the judges have to reframe this as this is not just a bunch of individual employment cases. This is taking a blowtorch to congressionally authorized agencies.

Anne: And something else that we've talked about is the spoils system. This idea that in the past, you know, presidents would fire, you know, the previous president’s crew and bring in his buddies, like, put them in charge. That's not what they're doing with these agencies. They are not going, oh, okay, we're going to give all the jobs to good MAGA folks.

Mack: They’re depopulating them.

Anne: They are just slashing and burning, and it doesn't matter.

Steve: Defenestrating.

Anne: Yeah. Deforesting.

Steve: No, “defenestrate.”

Anne: Oh, yes. Throw out the window, yes.

Steve: “Deforesting” would have been good with the other metaphor.

Anne: Yes. I thought you were good, no, that’ what I thought that’s what you were . . .

Steve: No, I wasn't that clever, no.

Anne: Just using a big, fancy word. Gotcha.

Mack: You missed the forest for the . . .

Steve: Windows.

Anne: Okay . . . But that's not what they're doing here, is. And, in fact, there have been, you know, the shocked Republicans who are like, “Well, wait, no, I was a good little Republican. Why are you firing me?” You know . . .

Mack: Or members of Congress, why are you letting go of all of these people that are in my district?

Anne: Right. Yeah. This thing that, you know, has been really good for my group, you know? Why are you . . . ?

Steve: Yeah. Well, I'm gonna argue that actually this is exactly the spoils system. It's just that instead of installing your cronies in the government, you sell off the government agency to your friends.

Mack: Which hasn’t happened yet, but ultimately could.

Anne: So, like the National Weather Service, they're getting it from the inside. And when they go, like, oh, this can't be run anymore . . .

Mack: They sell off the asset.

Anne: . . . Oh look, AccuWeather has a lot of employees that can take this, we’ll contract out to them. Okay. Gotcha.

Mack: Or AccuWeather decides, hey, we're going to be bigger. We can hire some of the meteorologists that have just been furloughed by --

Steve: Or, even better, a year from now, say, “Look, oh my gosh, the National Weather Service can't even do its basic job, but look at how bad they've been over the last year. We should privatize this.” I mean, whichever mechanism excuse you want to use.

Mack: Because Texas didn't do that to public education or anything.

Steve: Exactly.

Mack: One thing we should say, this is Friday, March 14, and as we speak, there is a continuing resolution going through Congress. It's apparently not actually a continuing resolution, but basically it was set up so that it's a poison pill, so that there are things in the bill that Democrats absolutely cannot tolerate. So in the House, it's a moot point because there's enough votes in the House that it passes, but in the Senate it could be filibustered. There's also enough Republican votes in the Senate for it to pass, but it could be filibustered, okay, where you just delay it until it dies, and it doesn't get passed. So if you delay it, if the Democrats decide to delay it long enough, there would be a government shutdown. And the Republicans think they can tag the Democrats with this, because the last times we've had government shutdowns, it has more or less, the people have, like, seen it to be the fault of the Republican Party, which every time, it really was. But this time, Democrats are worried because the only way to stop it is with a filibuster. And then there would be a shutdown. But if there's a shutdown, there is a overriding concern that with a government shutdown, that DOGE's efforts to fire government employees, sell off, auction off government facilities and buildings or whatever will just accelerate, and that they will get as much cut as they can during a shutdown, where those people will be told you will not be coming back. And so, the majority leader, no, I'm sorry, minority leader in the Senate for Democrats, Chuck Schumer, basically signaled that the Democrats would not be filibustering and that the continuing resolution would pass, even though there is stuff in that continuing resolution, that is absolutely intolerable for Democrats, but that he was not going to do a filibuster so that it could pass so that there would not be a government shutdown.

Steve: And there's another dimension to it, though, which is the, what is the point of congressional authorization of expenditures if the executive isn't going to follow them? You know, what does it even matter? So, I mean, in some ways, I would argue the CR is kind of pointless in that way, you know?

Anne: Well, quite frankly, a lot of Democrats are doing the same thing.

And we're getting divisions within that group.

Mack: Well, and in the House, when, you know, when Charles Schumer announced that, okay, we're not going to filibuster in the Senate, Alexandria, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, basically, and, you know, you should find a video of it because she is very straightforward and very passionate and really wants to go for Schumer to the throat. And, I don't know when his seat is up for grabs, but I would not be surprised if she goes for it. Because she expressed how not filibustering that the continuing resolution was absolutely unacceptable because of what it does, whereas Charles Schumer made the calculation that what DOGE would do during a government shutdown would be worse. But anyway, we have the internecine warfare among the Democrats, which is normal for Democrats, but it's also not helping them become the party they need to --

Steve: Well, in some ways it is, but honestly, the Democrats have held together pretty impressively over the last six, eight years, really, especially in the House, like under Pelosi. That was a rock-solid caucus. Not that they didn't disagree with each other. But as far as voting came, I mean, they held it together.

Anne: Yeah, Pelosi just came out against Schumer.

Steve: I can’t comment on Schumer. But, I mean, yeah, I've seen some interesting discussion kind of Inside Baseball-y, about how, look, we'd all like them all to be very angry, but also, at the end of the day, they have to work on legislation, and the way to work on legislation is to at least get a few Republicans to come over to your side. And you can't just, you know, scream all the time and get that accomplished. I mean, it’s not a simple situation.

Mack: I don't know the likelihood, though --

Steve: Yeah, no. Yeah, I'm not saying that I'm defending Schumer here. Honestly, I don't, I really just don't see the point of supporting any CR when they're going to ignore it anyway.

Mack: Yeah. And do what they want.

Anne: If they want a base to vote for them in two years, they’re going to have to start taking some big fucking actions, because who's popular right now? AOC. Nobody cares about Schumer.

Steve: No. Honestly, this is the one time I would have been in favor of government shutdown, because I think this is the time when you say no, this is all bullshit. And you pull the ripcord.

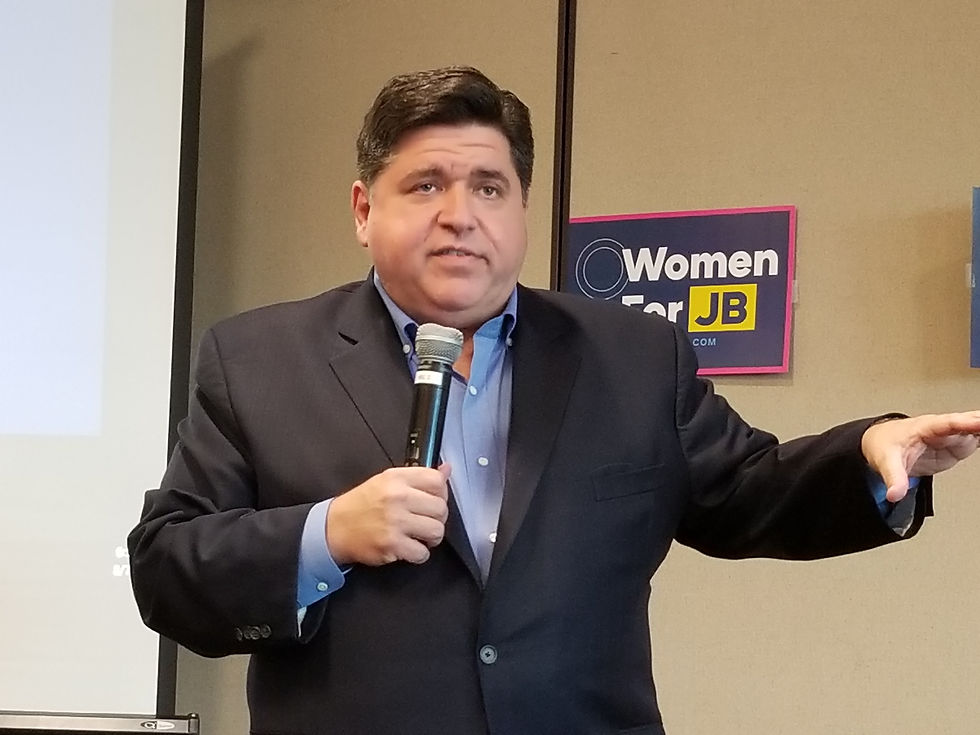

Mack: Another thing. Pritzker, who’s the governor of Illinois also put out a statement that was [a] very politically written statement, but it's almost a . . . he's throwing his hat in the ring, or at least he's putting this out there.

Steve: Sure. Not surprised.

Mack: And I just thought of that because you mentioned AOC, but I also think that in the coming years that Pritzker is probably going to make a name for himself on a more national level. And being governor of Illinois, I mean, he's got the opportunity to.

Steve: Yeah, I've seen a couple of posts from him, he has stood up nicely for governor.

Mack: No, they need to do, the Democratic Party needs to do, like, a major coordinated effort. Make the congressional elections for 2026 a national campaign in much the same way the Republicans did in 1994. In fact, they really should have been doing that. It’s like, why wouldn't you do that in 2022? Why wouldn’t you do it, you know, even though there's an expectation, okay, that's where the majority party is going to lose seats. Why not take the offensive? Why be defensive? And they need to work on that.

Anne: Good question.

[1:15:38]

Steve: But much like our cocktail, the “Dark and Stormy,” the outlook for the National Weather Service is uncertain.

Anne: That’s a valid effort, sir.

Steve: I try.

Anne: But we're going to drink the “Dark and Stormy.” We know that.

Steve: That's fine. Actually, it's great.

Anne: You want to try to segue?

Steve: Yeah, you got one? It wasn't good, but it’s the only one we had so far, so . . .

Mack: The National Weather Service is not just all of the data accumulated in the different weather service stations or whatever. It's the body of work and knowledge that this agency has developed over time and why we have what we do. And, you know, that legacy is, you know, part of what they do today. And, you know, I think it's a fair question with, and I know, you know, people that are in the field of meteorology, I'm not saying that, like, local weathermen and weatherwomen and people that work for even AccuWeather or the Weather Channel, I'm not saying that they wouldn't have a sense of that obligation, but the National Weather Service definitely has a sense of, you know, we're here to, yes, there's to help commerce and agriculture in the United States, but to save lives. And that's a pretty important part of their duty and their legacy. And we risk that if we're talking about breaking that up.

Anne: Yeah. I mean, I think there's something to be said about the history and the accumulation of knowledge, making something better, make something more strategic. And we are wholesale chucking a lot of our history to the side right now, in this country, and there's a history of, like, say, things like tariffs and alienating our allies and other things like that that have real consequences. In the past we saw it. And ignoring that past will only hurt us.

Mack: Certainly doesn't help us.

Anne: To have something with a legacy, to have something with a cultural history that is important, that should be protected and respected.

Mack: That's part of what makes, honestly, it is part of what makes America great. If we're going to talk about actual things that make America great.

Steve: Yeah. Well, and it's not just that there's a history, it's that that history is a predictor of future performance. You know, you have a National Weather Service who over the years has gathered data and built expertise and models and continues to improve projections and tracking and things. Do we want to keep the organization that has that successful track record or can it and move it to private industry because probably private market can do it better? That's not very reassuring, you know. So why would you throw out the thing that works?

Mack: That costs, relatively speaking, very little. Which if anything shows that they're not actually really interested in saving money.

Steve: And they're bad businessmen.

Mack: They're costing us money.

Anne: Well yeah. I mean, their track history with money. But, yeah, I mean, you think about if you’ve ever worked for a company or you've ever gotten a software update, you know, the whole business strategy is to always make new things, to always change it, to sell you something new. Because if it's good and working and fine as is, nobody buys a new thing. So, you know, having something that's established and works well and doesn't need to be updated every six months, that's not a good business model. It's a great safety model. But it's not a good business model. And when we're talking about something that literally will affect whether people live or die, which do you prefer? But these are business-minded people who are making these decisions.

Mack: Well, which are not, by the way, there are business-minded people that would not make these decisions that are good at business.

Steve: Yeah, these are business-minded, but a particular kind. Short, very short-term, very short-sighted, you know.

Anne: And it's about money. It's not about a business, per se. It's not about growing a business or making a product that means something. It's about money, money, money, money.

Steve: They're interest in the short term.

Anne: Which is why one of the ways that you can protest or act to show that you are dissatisfied with what they're doing is through money, and why a lot of people are participating in boycotts right now. And it is an effective method of protest.

Mack: One that has a long American history.

Anne: Yes.

Steve: Tea party.

Mack: Yeah. Actual tea party.

Anne: And there are already economic signs that it is working. If you look at the people who attended, the billionaires who attended, the inauguration, they are losing money right now.

Mack: Well, and Tesla stock. And that's, I mean, a lot of the people that own Tesla stock are investors and investment firms deciding what stock to buy in for the funds and stuff that they manage. And Tesla stock has tanked. And by the way, if the $400 billion billionaire is, if a lot of that money was stock valuation, I wonder what he’s worth now.

Steve: And let's take that as an example of a boycott being successful. I just, there was a report today about how many Tesla C-suite members and board members have been selling stock recently in the last few weeks. You know, they're dumping the stock in the company they work for. That is a sign.

Mack: Yeah, because what Elon Musk is doing is not giving them confidence that things are going to be good for the company.

Anne: So that is one thing you can consider, you know, as an action that you personally can take in these dark and stormy times—

Steve: Nice connection.

Anne: Thank you. I tried—is a boycott, you know, and boycott what you can. I mean, it's easy for me to boycott a Tesla. I wasn't going to be able to afford one anyways. But, you know, things like, you know, some people are boycotting Target since they repealed their DEI policies. Some people are boycotting Walmart because it's long history of supporting conservative political measures.

Steve: And counter pointing, like, Costco reinforced their DEI, and some other companies too.

Anne: Right. So you can vote with your dollar. Now obviously if, that's if you have the ability to do so. If the only store in your small town is a Walmart, you probably have to shop there. So something to consider is voting by brand. If you buy the Walmart brand, 100% of the profits go to Walmart. If you buy another brand that is sold through Walmart, yes, they will get a percentage, but some of that money will go to another company. Same thing with Amazon. You know, I still use Amazon, I admit it, because of the convenience factor. If I can buy something not at Amazon, I'm trying to do that.

Mack: That's why I went to eBay first, by the way, for the chicken book.

Anne: Well, good for you. I'm proud of you. But, like, you know, if you're looking for a book that's less obscure than perfect chickens, you can go to, like, bookshop.org or other --

Mack: Thriftbooks.

Anne: Yes. Or you can find thrift books. So there are options out there, and a lot of people are talking about them right now. So you can go and find advice if you need it.

Steve: A general rule of thumb there is if you can find a local store. That helps a lot. Frankly, I did some digging once on a topic about which company, like, gave money to which politicians. And I kind of basically found out for big corporations, they give money to all the parties.

Mack: Yeah, they do.

Anne: That’s a very fair point.

Steve: So you can't say I'm going to boycott Corporation X because they gave money to a certain party or somebody with a stance because they all did. So the only way you can really have that impact, if you want your money to go somewhere else, is to buy more local small business.

Anne: Yeah. That's an excellent point.

Steve: So that's a pretty safe choice.

Anne: And we got to be honest with ourselves. That economic hard times may be coming. This tariff thing is exactly, similar, it's very similar to the tariff thing that happened right before the Great Depression. Not it's saying it's gonna cause a Great Depression, I'm just saying that happened too.

Steve: Not the smoothest economic . . .

Anne: You know, inflation is already rising. The cost of eggs, I hear, is going up.

Mack: It is.

Anne: Perfect chickens notwithstanding. And so now would be a good time to be smart with your money anyways. So maybe look at ways you can cut back at spending to mega corporations is one way to go about it.

Mack: Yeah. Here's to the men and women of the National Weather Service and NOAA.

Anne: Yes.

Steve: Hear, hear!

Mack: Then thank you for the job that you do.

Anne: Thank you for your service.

Steve: Thank you for all you do.

Glasses Clink.

Anne Trominski was born and raised in El Paso, Texas, but now resides in San Antonio. She graduated from Trinity University after majoring in English and Communication. She spends her dull working hours as an editor for a major publishing company and her personal time as an oft-frustrated writer and amateur podcast producer. She has written two yet-to-be published novels, countless reams of heartfelt poetry, and has tried her hand at blogging a few times. Anne is also a gastronomist, amateur chef, and student of health science. She is a constant learner and explorer and likes to drop knowledge on others like it’s hot. Most recently, she helps disseminate social science info through the podcast Civics on the Rocks.

Comments